Eleventh Variation

Eleventh Variation

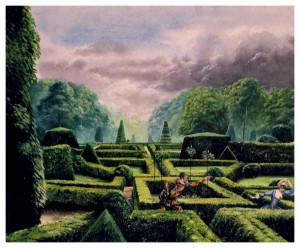

In their inevitable partiality, the most appropriate metaphors for interpreting the present-day company are no longer those based on classical management paradigms, but those that refer instead to the idea of the corporation as a labyrinthine work, spectacular and turned into a show, like a circus show, like a theatrical or cinema screenplay, or like a TV programme schedule, permeated by diffuse “new sentimental education”.

In the Shakespearean corporation it is remembered that the labyrinth is an age-old structure, but also the mother of all metaphors on individual and organization realities: what is the machine, the brain, the network and the organism (the founding metaphors of the classical management paradigms), but also the multiple personality of the present-day “mutants”, if not labyrinths? The labyrinth is a universal object, spread practically everywhere. This is demonstrated by the scrupulous mythological research of Kerényi (In the labyrinth, 1941). As a symbolic object, the labyrinth readily lends itself to representing the world with sufficient ideographic force to be applied to various levels of human existence. In particular, it is not difficult to make out an essentially labyrinthine structure in the world-famous Borgesian Library of Babel, complete with corridors and intersections, arranged in an infinite, multilevel manner. Here, the global metaphor of the world returns as a book and as a labyrinth with which modern culture is impregnated and that can be extended to the corporate universe. In this sense, labyrinths, works and corporations can be traced back to a schematic typology that distinguishes them, also under the profile of historical evolution, as polyvocal, rhizomatic tree-like unicursals.

However, the most evident characteristic of current society, it being a “society of the spectacle”, gives rise to an important consequence: the works that better metamorphise it, also in its corporate variant, are representations, like theatrical or cinematographic ones or, for those that appreciate the genre, circus shows.

The centrality assumed by project-based works in almost every single business, in each phase of the production process, strengthens the validity of this interpretation. Today, therefore, the leader must be simultaneously author, producer and actor, also because he/she is continually called upon to come up with a new script, to direct the show’s project in which they are acting and then, when the season is over, pass to another project, another show, another objective. Change does not worry the producer: he/she knows that after a show there will simply be another, because the new economy of knowledge does not allow repeats. In this sense, the preferred organizational model is the theatrical company. Each time, it is formed by a cast chosen for the occasion and ready to rearrange itself in a completely different manner for the next show, or rather the next project.

The roles are decided each time with different points of view and it is each individual’s responsibility to find the best way of relating to the given role. This does not mean that work is always enjoyable, exciting and new. As actors well know, there is always a moment of stress (relationship with the new script or project), a moment of emotion (development), a moment of boredom (two hundred repeat performances of the same role) and a moment of mourning (leaving the project). To this is added the possible anxiety regarding the next project. Thus, even in present-day corporations, the cycles of stress, emotion, boredom and mourning follow on from project to project, business after business, innovation after innovation. Continuity is represented by the permanence of discontinuity. As in the theatre, the corporations present a backstage and a by-play and consequently demand show figures and figures with first-rate “backstage” skills. For both roles, the GANTT and a sane quickness of reflex substitute the assembly line. As in the corporation, in the theatre one must never lose sight of the details, even while maintaining sufficient flexibility to respond to the contextual solicitations, which is different for each performance (size of the stage, the available equipment – lights, microphones, machines – the typology and number of paying members of the audience, and the physical and mental state of the individual members of the cast), and there is no possibility of duplicating organizational models, other than in very broad formats. Looking at it, the theatre metaphor overlaps that of the Platonic Symposium, which is similar in many respects to a recital of the Comedy of Art, where every person improvises his/her part according to the scenario and measures himself/herself against the others and the public. Both of the metaphors serve well to depict the idea that contemporaneity must first of all clear the field of the waste and ruins of industrial modernity: the obsession of productivity and wealth, the maniacal precision of closed systems and the paranoia of having everything under control. It must transform the place of work into a banquet; where it’s known how to distinguish between the machines and the people (substituting the organization chart with the people chart) and to use people to do the extra and different things that machines are incapable of. If we integrate the element of geographic dispersion into this framework, the reference metaphor becomes the television network.

The corporation produces a representation of reality for the customer that is the result of realizing plants, or rather different television studios, each of which is characterized by the model of a temporary, project-based group. Thanks to common computer and telematic architectures, the productions set up in the system and integrated by the central manager, or rather the programme schedule manager, constitute the global corporate result.

Finally, each production, although taking into account the increasing importance of visual communication, inevitable becomes dialogue, the discourse, the word. The great passage from decision making to sense making is made via the word, which requires a new relational capacity at a specific level and a new “sentimental education” at a more general level. The new relational capacity should include not just the ability to debate with others, accepting the insuppressible oneness, diversity and alterity, and considering every meeting, from two people to the small group to a large group, as the meeting of distinct absolutes, but also the ability to converse with one’s inner self, in the conviction that only a true love for oneself can generate real love for the others. If we are always in the search of self, we will become capable of caring, of relationships in which someone assumes the responsibility of working for the growth of the other.

Go to Intro

Humanistic Management 2.0

- Home

- Origins of Humanistic Management in Italy: the ockhamist organization

- Agip Library

- The Shakespearian Company

- The Humanistic Management Manifesto

- Nothing twice. The Management seen through the poetry by Wisława Szymborska

- The Humanistic Management chair

- The In-Visible Corporation

- Web Opera

- ideaTRE60

- Postmodern Alice

- Founder & CEO of Humanistic Management 2.0

- News

- About Marco Minghetti

- Selected Excerpts

- Home

Feed RSS Subscriptions

Email subscriptions

About

Social media

Tag

Alice Alice in Wonderland Alice Wonderland Carroll Shakespeare Postmodern Baricco Deleuze Digital Awards Frank Kermode gary hamel George Steiner Hamlet Harold Bloom humanistic management labirinth Looking Glass management Management 2.0 Hackathon map Marco Minghetti poetry Postmodern Raymond Queneau Shakespeare Snark Stevenson Wislawa Szymborska Wonderland

Latest Comments