Tenth Variation

Tenth Variation

The leader is an author, a producer and a leading actor. At the same time he/she expresses a “weak” leadership, the essence of which is not to manage, but to let the processes, the activities and behaviours “flow” along a course that does not have a clear goal: do not undertake to produce more, but rather understand the what, why and wherefore of producing.

The leadership of a “humanistic” manager is primarily based on the ability to foster and share reflection on the means and risks for doing things (shared planning skill). In addition, the sharing of knowledge as a font of possible avenues of exploration is important, the specificity of which must be recognized, namely the need to render its usage dialogical and not hierarchical, not one-way: knowledge cannot be subjected to hierarchy (because it would lose its effectiveness). It must therefore be acknowledged and valorized even if it is often inconvenient and not of immediate use.

More in general, the difficulties created for the old hierarchies are strictly related to the failure of the concept of order underlying the scientific paradigm of management. On the political plane, to have a Vision, indicate a goal and supervise the organization’s institutional aims does not mean that order should be intended as the predetermined plan of who, by statutory right, governs the organization: precisely, the manager. And the parallel idea that, as the opposite to order, only chaos exists, and therefore the disintegration of the organization. This conception brings with it the need for command (through which the manager imposes his order on the organization) and control (exercised for checking that the order is achieved and maintained).

In a turbulent context (that is subject to extremely rapid changes and characterized by extreme competitiveness), the ability to receive the maximum number of external stimuli and to promptly interpret them, in order to adopt the most appropriate profile each time, seems instead to be inversely proportional to the intensity of command and control. The winning organization – suggests Kevin Kelly in his programmatically entitled book Out of Control – a) is a network made of autonomous and cooperating modes, b) does not report to a centralized command function, and c) is capable of self planning.

The aporia of humanistic management is that of a manager capable of losing control of the organization, whilst knowing how to conserve guidance. Maintaining guidance means to support the mission and the organization’s institutional role, defending its integrity, to guarantee the discharge of its social responsibility and to support individuals under the strains deriving from personal self-development practices. To lose control means renouncing to the claim of determining an a priori order and supervising it in the smallest detail. This does not mean chaos getting the upper hand and the disintegration of the enterprise. Without over emphasizing Kelly’s idea, which amongst other things is heavily influenced by a biological-organicistic type of “scientific” paradigm, it is certainly true that the organization has an order of its own. To be more precise: an order is given, it is found within it and it is left free to act within the limits imposed by the need to maintain the general form, the specific identity determined by factors such the dimensions, the type of activity, the level of internationalization, the legal, political and social systems with which it interacts, and it own story, which is actually the story of the individuals that have created it and recreate it each day. Vice versa, the adaptation to an order that is predefined and declined in terms of rigid and all-pervading control instruments, evaluation and control risk atrophying the differentiating force of the organization, which is proportional to the level of autonomy of its synapses, making it more vulnerable. The model is better understood passing from the political plane to the essentially epistemological one. If we must think of the organization as a sense-generating collective force and a privileged discursive context, according to the sensemaking perspective of Karl Weich, it clarifies its objectives and the roles of the parties involved – let’s say it makes its own project clear – only at the end of the discursive process, not at the beginning. The manager, therefore, ceases to be the one who dictates the senses to the rest of the organization, the one who supplies the correct interpretation of the objectives, the roles and the functions, perhaps through a more or less manipulative process of envisioning, which must be substituted by an approach closer to Socratic maieutics. In this case as well, we can talk of renouncing to the proposition of a detailed (cognitive) order, substituted by the diffusion of a “Vision” that allows, via the reflective and dialogic activation of everyone working in the enterprise, the accomplishment of the twofold primary management task: to favour the achievement of the organization’s objectives, combining them with those of the self-realization and self-development of the people that work within it.

It is easy to sense how complex it is for contemporary management to deal with the aporia of the “guide without control” and throw away a fair part of that instrumentation that until now has guaranteed the exercise of power. The humanistic approach has its own coherence with respect to managerial profile described up to this point, in the sense that it refers to a discursive tradition in the construction of truth, which has its own foundation in the ars rhetorica. To that end, the leadership can and must carry out a coherent series actions aimed at keeping a certain level of symbolization constant within the organization for which they are responsible.

The effectiveness of a leader is based on his/her capacity to make the activity important for those that have role relationships with him/her, not changing their behaviour, but giving them the sensation of understanding what they are doing and, above all, articulating it in a way that they can communicate the senses of their behaviour.

The dialogicity that goes beyond the hierarchy thus forces leaders to move with assurance, entering and leaving different roles. Or playing more than one at the same time. Vittorio Gassman said that he had touched his artistic limit in moments in which he had decided to be both producer and actor in a show. Great producers, when they decided to be the interpreters of their work, and vice versa great actors, when they have also wanted to be producers, have often met with failure. To be simultaneously creative designers, producers and lead players is challenging and complex. Still, this is exactly what is requested of managers today.

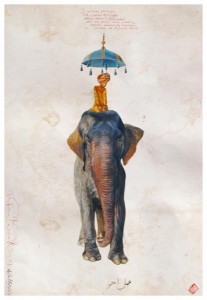

But what does one do to become author, producer and leading actor at the same time? Enriching one’s perception and points of view. It is a question of seeing the corporation through a set of cameras that offer a number of perspectives (close up and panorama, moving images and optical effects) and always pointed on oneself. In short, to substitute bureaucratic control with constant monitoring, careful observation of the numerous levels of organizational reality. It is control with care, or rather comprehension of the needs of the individual persons that take part in the project. Summarizing, “weak leadership” is established, characterized by the ability to “ride the situation”. The words of Tolstoy in War and Peace, where Kutuzov is contrasted with Napoleon, are exemplary. Today, Napoleonic leadership is tendentially ineffective and even harmful. It is based on delusions of omnipotence. The tension against omnipotence is harmful. The illusion of being a deus ex machina, when faced with complex systems – of which we are part and that we can never observe from the outside – is fallacious. The Napoleonic illusion is based on the existence of best practices, of the optimal solution. Whereas the nature of complex systems only contemplates sub-optimal solutions – many quite good, but none the best. There is no cause-effect relationship between the manager’s choices and corporate practices. Results do not follow from inspired choices by the manager. Nor are the manager’s decisions direct responses to the organization’s requests. At the heart of successful organizations, only synchronisms watch over things. Managerial success originates from an encounter that cannot be forced, but by a happy – apparently casual – coincidence between the behaviour of the manager and the spontaneous behaviour of the organization. Management is the timely foretelling of what is feasible and appropriate.

Go to Intro

Humanistic Management 2.0

- Home

- Origins of Humanistic Management in Italy: the ockhamist organization

- Agip Library

- The Shakespearian Company

- The Humanistic Management Manifesto

- Nothing twice. The Management seen through the poetry by Wisława Szymborska

- The Humanistic Management chair

- The In-Visible Corporation

- Web Opera

- ideaTRE60

- Postmodern Alice

- Founder & CEO of Humanistic Management 2.0

- News

- About Marco Minghetti

- Selected Excerpts

- Home

Feed RSS Subscriptions

Email subscriptions

About

Social media

Tag

Alice Alice in Wonderland Alice Wonderland Carroll Shakespeare Postmodern Baricco Deleuze Digital Awards Frank Kermode gary hamel George Steiner Hamlet Harold Bloom humanistic management labirinth Looking Glass management Management 2.0 Hackathon map Marco Minghetti poetry Postmodern Raymond Queneau Shakespeare Snark Stevenson Wislawa Szymborska Wonderland

Latest Comments