Fourth Variation

Fourth Variation

Apollonian modernity organized according to rules of scientific management is an extraordinary source of knowledge creation and replication: it finds itself in difficulty however when the complexity, set in motion with increasing rapidity by the “sorcerer’s apprentices” of Fordism and their epigones, is greater than the available means of control.

Nearly thirty years have passed since Charles Handy first sent to press what was to become a classic of management literature: Gods of Management. In this work, the organizational styles and corporate culture are traced back to four archetypes, identified in four gods of Greek mythology. Yet the true contrast is between the Apollonian model (in which Apollo, god of order and bureaucracy, becomes a symbol of the enterprise based on control correlated with the rigid definition of duties) and the Dionysian one (in which creativity is preferred to standardization, diversity to homologation and the individual to the machine). Already in 1978, Handy denounced the growing crisis of the Apollonian companies taking shape, focused on the search for ever-greater size and consistency, but destined to clash with the need of individuals to have more room for personal expression.

It is a conflict that Apollo cannot win. If companies want to survive, they must adapt their management philosophy to a stance more in keeping with the needs, aspirations and attitudes of individuals. In the new mix of gods that ensues, Apollo will be less dominant and less inhumane. The relevance of Handy’s intuitions are under everyone’s eyes, but the Apollonian model continues to be prevalent, in spite of so much rhetoric regarding the crucial importance of “knowledge workers”, of continuous training and of the “centrality” of human resources, the practical translation of which should cause the enterprise to acquire increasingly Dionysian characteristics.

Another contradiction of the contemporary enterprise, linked to the previous one, is that the opposition between “clones” and “mutants is cited” in the Shakespearean Corporation. To understand it, just call to mind the idea that a “war for talent” is under way: an idea introduced by the big international consulting companies to sell a series of services (selection tools, retention policies, tools for identifying high-potential staff, etc.) to companies aimed at attracting and retaining the best resources. In real life, we witness the failure of many of the programmes started by corporations in this field. The motive should be sought precisely in the fact that they are, to a great extent, still rigidly Apollonian and are based on organizational and management models adequate not for exploiting talented individuals and ingenious personalities, but rather for treating people like clones, rational repeaters of tasks and duties. The “clones-mutants”, or rather “human resources-persons”, opposition is therefore a fundamental divide between humanistic management and scientific management. We can cite as an example from an article, written by Sidney G. Winter and Gabriel Szulanski. The article is entitled “Replication as a strategy”. The authors tell us that “replication, a familiar phenomenon like the ‘McDonald approach’, is a strategy pursued by a large number of corporations active in at least sixty fields”, complaining about the fact that “although that of replication is becoming one of the organizational forms of our time, it has been forgotten by organization scholars”.

In addition, for Winter and Szulanski, “replication strategies have a certain similarity to the diffusion of innovations in an organizational population because they entail far-ranging knowledge transfers”: they are actually “based on the creation of outlets that can automatically produce their product or service”. The most glaring case is given precisely by the fast foods, “which produce volumes of food five times greater than those of an average restaurant and which mainly use standardized procedures designed for unskilled workers”.

Behind this reasoning, there is the conception of scientific management intended as an evolution of the previous mechanism of governing complexity, inaugurated by modernity and in force throughout the 19th century. This mechanism consists in delegating decisions to automatisms of great power such as technology (technological optimization), the market (economic optimization) and the constitutional state (compliance with regulations). Three reducers of complexity that have the characteristic of being abstract and self-referent, in the sense that they choose the possible alternatives of production and life according to criteria within each sphere of action (technological, economic, regulatory) and, obviously, are one-dimensional, being related to technical, economic, political parameters etc., which do not integrate with each other, but dominate different areas of the environment and social behaviour. Each sphere of action aspires to present itself as a form of objective rationality, unquestionable because it is based on objectively measurable optimizations.

Self-referent automatisms are formidable knowledge creation and replication tools. The productive force of modernity consists in this privileged relationship between knowledge innovation/replication needs and the social forms that make it possible. In the pre-modern world, knowledge was immersed in human and social humus organized around the hierarchical principle of knowledge by authority, revelation and tradition. Knowledge existed, but it was not able to easily break away from the old handing down by history and when it became innovation, it was not able to translate it into economic value, due to validation/replication difficulties. The result: there was no space for investing in knowledge, or rather for employing men and means in the research, experimentation and the systematic application of the new and the possible. Instead, the automatisms that emerged with modernity “free” the energies from the previous subjections and provide, according to one-dimensional measurement and optimization criteria, a suitable environment to reform and to replicate innovative knowledge that “works”. The economy therefore starts to invest in knowledge production/propagation and makes it a productive force. Even if there is some disruption, the complexity of the world is broken down and placed at the service of a production criterion. In the historical design of early modernity there were however two weak points.

Firstly, modernity uses knowledge to feed the three self-referent automatisms set in action, but knowledge is not something easily domesticated. It becomes a technological resource, an economic resource and a regulatory resource, but, if one wants “true” knowledge, it cannot be bound to these three criteria. In order to be reliable, knowledge must be critical, or critical metaknowledge accepted, which is not aimed at generating useful effects in the three prescribed fields, but, if anything, to check the existing structures and make them dynamic. Knowledge is also a potent principle of destructuring, because it transforms all of the structures into provisional results, in constructive processes that must be continually reinvented, preventing their stabilization. Therefore, knowledge systematically generates a complexity of variants, changes and uncertainties that exceed current usage requirements.

Secondly, while early modernity, that of the 19th century market economy, quickly discovers its limits in handling complexity, succeeding in mechanizing only simple operations, the scientific management that Fordism fields in the 20th century tries instead to govern complexity by synchronizing technological, economic and regulatory knowledge in large-scale expert systems, in which the various skills needed are regulated and cultivated at an appropriate level of specialization. The problem is that the three separate mechanisms of technology, economy and regulatory control were built to be self-governing, unbeatable in partial production (in the individual fields), but not coordinated with each other. They thus give rise to divergent impulses and remain unmanageable in any situation that requires complex and simultaneous changes in all three spheres. In this way, the passage to a different organization of the automatisms comes into being in the 20th century: that based on the connective role of management. Management becomes a principle of connection between spheres (which remain autonomous and independent): its task is that of directing technological advancements, economic choices and regulatory behaviour, of both the state and of large organizations, in a coordinated (programmed) manner.

Thus, scientific management is technological know-how, economic rationality, and organizational and institutional power, all together. It resubjectifies modernity, putting back man’s orientative knowledge in the three points of intersection of the autonomous mechanisms that feed modern “progress”. Yet, at the same time, it limits this resubjectivation to a technical, neutral role: because of professional ethics and the concrete restrictions that it moves within, management “must” serve the right development for the three mechanisms it intertwines, without distorting the function to its own advantage. Delegation to automatisms becomes delegation to expert systems, namely the public and private technostructures that concentrate know-how, economic means and decision-making power.

Expert systems add negotiation with the various stakeholders to the self-referent force of the mechanism they are under (technology, market or regulations), or rather a principle that aims at completing the predictive and control powers of the initial automatisms, because the managers of organized capitalism, the Fordist model, need one thing above all else: stability.

In a certain sense, scientific management is the natural fulfilment of modernity: it provides neutral negotiation for completion of the predictive/regulatory force provided by the three basic automatisms of modern society. Yet, it has a weak point: its political function can “consume” more productivity than it creates. The power exercised over the technostructures, even in the “common” interest (not always so), obviously sparks off a counterpower, because interests organize themselves to have more influence and, in this way, expropriate the automatisms and challenge the effectiveness and autonomy of management in its role of “scientific” (or neutral) mediation.

The crisis occurs (from the 1970s onwards) because in the end the complexity set in motion by the scientific management of Fordism turns out to be greater than the available means of control, and also because a situation of poverty is left behind and therefore one of subjection to necessities. From a certain moment onwards, the legitimation of technological, economic and regulatory rationality can no longer be achieved on the terrain of measurable, objective “convenience”, but rather on the terrain of creating value that regards desires, emotions, and individual and collective imagination. The social subjects can no longer delegate to others the development of ways of life that depend on the aspirations and actions of each person, who position themselves in the numerous, distinct contexts that everyone has in mind and which the automatism or expert is not able to see and, in any case, does not intend to consider in detail.

Go to Intro

Humanistic Management 2.0

- Home

- Origins of Humanistic Management in Italy: the ockhamist organization

- Agip Library

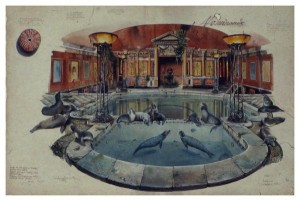

- The Shakespearian Company

- The Humanistic Management Manifesto

- Nothing twice. The Management seen through the poetry by Wisława Szymborska

- The Humanistic Management chair

- The In-Visible Corporation

- Web Opera

- ideaTRE60

- Postmodern Alice

- Founder & CEO of Humanistic Management 2.0

- News

- About Marco Minghetti

- Selected Excerpts

- Home

Feed RSS Subscriptions

Email subscriptions

About

Social media

Tag

Alice Alice in Wonderland Alice Wonderland Carroll Shakespeare Postmodern Baricco Deleuze Digital Awards Frank Kermode gary hamel George Steiner Hamlet Harold Bloom humanistic management labirinth Looking Glass management Management 2.0 Hackathon map Marco Minghetti poetry Postmodern Raymond Queneau Shakespeare Snark Stevenson Wislawa Szymborska Wonderland

Latest Comments