Second Variation

Second Variation

The steamroller mechanism of modernity, a productivity machine that relieves the actors of responsibility and weakens policy, is already born with chinks, invisible on the surface, which irreparably undermine the foundations of that scientific management of which it is one of the extreme expressions.

Without exhaustive ambitions, it can be affirmed that modernity is the patrimony of ideas and practices that we have received by inheritance from the Enlightenment and from the French Revolution. Modernity, which contains the traits of scientific rationality and technology, distinguishes itself with the discovery of production during the first industrial revolution. At the level of civil societies, it coincides with the birth of the nation states throughout the West and the beginning of democratic forms of government. Modernity still harbours a deep faith in linear improvement, in limitless progress, which Positivism, Enlightenment and phenomenology of the spirit coherently nourish. Modernity as an ideology thus finds its seminal kernel in what took place in Europe between the last quarter of the 19th century and the outbreak of World War I. In those forty years, modernity defined itself as an ideology and, as such, earned the consensus not just of the elite, but also of vast strata of the population. Thus, modernity is: (ideology of) progress, technology, emancipation, industry, city … Whilst pre-modern is: tradition, metaphysics, conservation, agriculture … The factory is modern. The workshop is pre-modern. Above all, it is the dichotomic approach that is central in the construction and consolidation of the concept of modernity. From organizational experience, the most important dichotomies are those between strategic planning and action, between rationality and emotion, and between actuality and possibility. However, modern is, more in general, the time of separation, a direct consequence of the divisions triggered by science in the 16th century and which recognizes not just a symbolic reference in Cartesian meditation. On this basis, everything is subjected to the scrutiny of self-referent rationalities that, by definition, are not contained within the order inherited from history. The modern world (Coleman says) must be rationally reconstructed: therefore, the previous hierarchies must be put to the test, deconstructed and forced to justify themselves. Nevertheless, modernity is not the kingdom of fluidity, because it proposes its own rigidities and its own criteria of order: in addition to the separation of the spheres, the construction of rational (and hence rigid) social orders in each of them and delegation of the reduction of the complexity that previously fed the dynamic world to automatisms.

Paradoxically, however, modernity is marked by the progressive emergence of a crisis of certainty in the fundamental dichotomy – that between “reality” and imagination. As far as this is concerned, we could say that the steamroller mechanism of modernity, a productivity machine that relieves the actors of responsibility and weakens policy, is already born with chinks, invisible on the surface, which irreparably undermine the foundations of that scientific management of which it is one of the extreme expressions. Let’s look at the founding works of modernity. The doubt regarding the structure and the actual ontological consistency of what is real is at the centre of the plays that Shakespeare wrote in England at the end of the 16th century and the early 17th – it characterizes the birth of the novel in Spain with Don Quixote, appearing a few months before King Lear, in 1605 – it induces Galileo to read the mathematical language in which the “great book” of nature is written, confuting, in the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, dating back to 1632, that the Aristotelian conception of the world is also, cautiously, like “pure hypothesis”, whilst the poet Calderón de la Barca proclaims in 1635, without mincing words, that “life is a dream” – it triggers the founding of the new philosophical method by the Descartes, who published his Discourse on Method in 1637. One thus understands the extraordinary luck in this period of political conceptions based on comparison with the “non-place” introduced, with anticipatory intuition, a century earlier by Thomas More on the model of the Platonic Republic, but which only now is visited by many illustrious travellers: it is sufficient to mention Campanella’s City of Sun, 1623, or Bacon’s The New Atlantis, published posthumously in 1627.

The divide between the humanistic and scientific approaches, which deepens over the course of the centuries until it becomes an abyss, depends, in the last resort, on the response proffered to the question on the ontological consistency of reality. This process runs parallel to the separation – ratified by the methodological debate developed from German historicism – between natural sciences and human sciences, with the correlated indication of different ways of producing from the two knowledge-generating scientific typologies, simultaneously premise and consequence of the separations existing in the organizational practices of what is modern; a distinction that is inspired by the need to define the terms of knowledge and to provide guarantees for its validity.

The natural sciences will be characterized by results of greater objectivity and by their working through cognitive processes of a random nature. The human sciences will be characterized by a more personal involvement of the researcher and by being based on the cognitive mechanism of understanding. Yet understanding, essentially an empathetic process, is a process that indicates, via the loss of the separation between natural sciences and human sciences, a new epistemological stature, characterizing contemporary culture to the point of allowing “that ‘second level’ of reality that can escape hyper-rationalistic processes to be caught”.

However, the journey that leads to this result is slow, is not without contradictions, and has stops and restarts. In 1925, the mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead showed in Science and the Modern World the deep-rooted links that bind the history of science and the history of literary movements. Even in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the majority of poets, not unlike the astronomers and mathematicians, came to see the universe as a machine, docile towards the laws of logic and open to a rational interpretation: God was left the part of the clockmaker of which the clock postulates the existence. This conception also extended to society: for Louis XIV as for the American Constitution, a planetary system, a perfectly regulated mechanism. To say it with Koyre’s famous image, they were the extreme consequences of man’s entrance, during the Renaissance, from the world of approximation to the universe of precision. From that point on, commented De Masi, “precision will be everything”. Human nature was examined with the same spirit of lucid rationality, searching for its laws. Newton’s theorems thus found an equivalent in the masterpieces of “Classicism”: the geometric dramas of Racine, the harmonious couplets of Pope. Yet as time went by, the idea of a pre-arranged mechanistic order starts to appear as a constraint to the eyes of both poets and scientists. Why exclude too large a part of life, or rather, offer an image of life that does not correspond to actual experience. Romanticism thus appears as a reaction against a certain way of intending scientific research. There are aspects of experience that cannot be explained according to the theory of a perfect world, regulated like the mechanism of a clock. The universe is not a machine. It is a more complex, more mysterious and less rational system.

Poe lives and writes in this time. Comte publishes the Course of Positive Philosophy in 1830. In 1847, George Boole presents his logical-formal notation system aimed at allowing the “calculation of thought”. In 1839, Darwin publishes the Naturalist’s Voyage Round the World. (Poe had published Gordon Pym, an adventure novel, the year before. Both Darwin and Poe, scientist and poet, had got the idea and inspiration from A Voyage Towards the South Pole by Captain Weddell, who in the summer of 1822, in the South Seas, had reached places never before touched by man). Yet Abbott Lawrence, who did not limit himself to managing his foundries, as he also financed Harvard University, wasn’t satisfied. The university was firmly in the hands of traditionalist intellectuals; the sciences – physics and chemistry – were looked down on; least of all was there space for teaching arts and crafts. And so – still in 1847 – Lawrence (an exponent of that America whose hero was Benjamin Franklin, an eminent scientist, but also a businessman) writes to the University treasurer, “Where should we send those who intend to devote themselves to the practical applications of the sciences?”.

Harvard opposes the requests. A group of entrepreneurs and intellectuals then decide to create a new institution. The motto, soon found, well expresses the aims: Mens et Manus, “mind and hand”. However, a suitable name to indicate the originality of the approach is still missing. It will be proposed by Jacob Bigelow, a heterodox lecturer, for years a supporter of Applications of Science to the Useful Arts. Bigelow proposes a word that the Ancient Greeks already new. Technologia meant “the systematic treatment of an art” (techne – which probably derives from the Indo-European root tek-, “to make” – meaning “art”, “craft”, and logos meaning “word”).

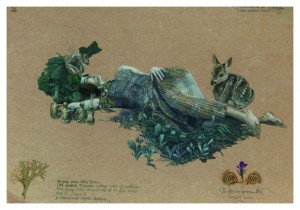

Thus, in 1865 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is founded. And it imposes an attitude: new opportunities of industrial development should be sought in the new frontiers opened by science, more than in the field of traditional crafts. Hence, from laboratory work, no longer reserved to elegant and abstract experiments, the electric and the chemical industries spring up between 1880 and 1920. The electronic and the nuclear industries will then follow. Rational and positive science triumphs, but shows its limits when it confirms there is a net separation between Real and Imaginary: even though, unlike what took place in the Middle Ages, it concentrates everything on the supremacy of earthly “reality”, founded on the ability to dominate nature with technology. Art and philosophy, instead, increasingly tend to consider the world as an inextricable enigma, a “folly”, gradually losing the hope of extracting a meaning for man’s existence, whether located within the scope of a divine dream, as for Berkeley, or a nightmare of Will, as for Schopenhauer. The situation will further worsen after Nietzsche decrees the passing of the Dreamer. The Musils, the Kafkas, the Joyces and the Picassos will multiply, all interpreters of a human existence reduced to an indecipherable dreamlike vision arising from the death sleep of whichever God. A conception that, on the other hand, has also contributed to the exploration of the sub-atomic world by physicists, commencing in the first decades of the 20th century. A rapprochement between science and art, based on the understanding that there are unknown lands and seas around us and within us, has thus been produced.

Today, the need is increasingly felt for overcoming the afflictions resulting from the widespread sense of inadequacy and insecurity due to the disintegration of the world’s sense of unity – the entropy-kipple with which P.K. Dick is obsessed. To that end, it is necessary to renew the typically humanistic idea of a man who responsibly and freely self-determines himself, recomposing the fragments of his kaleidoscopic identity through a continuous process of dialogue with himself, but also with and “for” the others; of reflection on his means and his ends, even with the awareness that logic forces us to have a partial vision of things. Like the Love celebrated in the Symposium, the complete giving of self to another “which contributes to overcoming the distance between men, so that the Whole is ordered and united within itself”, so does knowledge demand, wrote Plato in the Seventh Letter, “a long coexistence and common work around it”. It is a journey that must be repeated often “uphill and downhill” until “the spark ignites and the fire in the companion’s soul lights”. Slips, coincidences, intuitions that take us beyond “scientific” reason. In those territories in which the poets, more than anyone else, move with ease.

Go to Intro

Humanistic Management 2.0

- Home

- Origins of Humanistic Management in Italy: the ockhamist organization

- Agip Library

- The Shakespearian Company

- The Humanistic Management Manifesto

- Nothing twice. The Management seen through the poetry by Wisława Szymborska

- The Humanistic Management chair

- The In-Visible Corporation

- Web Opera

- ideaTRE60

- Postmodern Alice

- Founder & CEO of Humanistic Management 2.0

- News

- About Marco Minghetti

- Selected Excerpts

- Home

Feed RSS Subscriptions

Email subscriptions

About

Social media

Tag

Alice Alice in Wonderland Alice Wonderland Carroll Shakespeare Postmodern Baricco Deleuze Digital Awards Frank Kermode gary hamel George Steiner Hamlet Harold Bloom humanistic management labirinth Looking Glass management Management 2.0 Hackathon map Marco Minghetti poetry Postmodern Raymond Queneau Shakespeare Snark Stevenson Wislawa Szymborska Wonderland

Latest Comments