First Variation

First Variation

A phantom roams the corporate world: humanistic management. A new way of doing business with respect to both the traditional canons of scientific management and the models proposed after Taylor, united by an ostensible scientific nature, as they follow, by analogy, the paradigms that asserted themselves in the physical or social sciences.

The history of management is recent: although its origins are embedded in works such as The Wealth of Nations (1776) and in the experience of the industrial revolution, it establishes itself as a separate discipline at the turn of the 20th century, with the works of Taylor and the practices of the Fordist factory. This is where scientific management is rooted, which had the merit of representing a special point of view, specifically characterized by an extraordinary constructivist and interpretative capacity of organizational reality and experience. At production level, the references have been seriality, standardization and specialization of work and duties – at trade level, the mass-market, and the tendency towards the product and quantity. The organizations – both those with a precise economic objective and those of public service and, in general, the large bureaucracies – have been guided by cultures and operating mechanisms based on the centrality of command, on an obsessive attention to execution processes. The cognitive model below is definable by the maximization of results in the least possible time, by the reduction of any variance, by the relinquishing of personal responsibility for the end result and by functional triumphalism, a mirror of the systematic negation of relational indispensability with the other.

The organizations inspired and managed through the paradigmatic perspective of scientific management place themselves as closed collective subjects, with a strong anticipatory capability and a linear/sequential vision of the decision-making process. The communicational model is the one-way type, “roger-over”, or rather “roger-over and out”; the technological solutions are those that can be standardized and incorporated in a product stabilized for its commercial life cycle. Many possible innovations are neglected, not just for commercial, but also production reasons (they are extra-standard). The cultural attitude is that of conformism to the solutions established as the most efficient and which are capitalized like a thesaurus.

The inadequacy of this procedure is obvious when faced with a “complex” world, that is to say a plural one, and also in rapid and continuous change in time and space, both remote and at hand. It should also be considered that management, as a “science”, cannot be limited to Taylorism. An effective summary account of its successive evolutions is traced in the masterpiece by Gareth Morgan, Images of Organization, in which a review of the main 20th century “managerial paradigms” is given. If Taylor looked to the mechanics, Chris Argyris, Frederick Herzberg, Douglas McGregor and others, after the historical studies of Elton Mayo in the twenties, have proposed an organicistic, biological paradigm; later on, paradigms inspired by cybernetics, sociology, psychology, up until the most recent ones taken from complexity theory, have followed one another. As Morgan had sensed, a metaphor (the machine, the organism, the brain, the network,) acts behind each of these descriptions: very useful for certain aspects, but due to its nature, also a generator of distortions. To say, “that man is a lion” serves to denote a characteristic, courage: nevertheless, “the man referred to here does not have a fur-covered body, nor four legs, not even sharp teeth and, least of all, a tail!”.

Each interpretation of the corporation starting from a “managerial paradigm” constructed by analogy on a science but which, in the last resort, is a more or less complex declination of a metaphor, thus brings with it limits and contradictions. In addition, the same scientists have underlined for a long time that the observed world and the observer interact. “The world appears as a complex web of events, the different relationships of which alternate, overlap or combine with each other, thereby determining the structure of the whole”. So wrote Werner Heisenberg regarding his field of work, theoretical physics. What is true for the physics of the 20th century seems even truer for the perennially temporary world that we have before our eyes today. To move around in which by fixing a univocal interpretation is pointless and actually damaging, because reality reveals itself in ever-different forms. It becomes important to search for training models able to interpret the new, finding the representational models precisely in that which is new, and continually constructing and reconstructing them. As soon as the habit of looking for the foundations is interrupted “and you learn to adopt a ‘let things slide’ attitude, then the natural characteristic of the mind to know itself and to reflect on its experience can finally emerge”.

Finally, the “scientific” paradigms proposed in managerial literature are paradoxically characterized by an intimate “pseudo-scientific nature”. For thousands of years, mainly rhetorical experts such as Gorgia da Lentini, Aristotle, Isocrates, Cicero and Saint Augustine have occupied themselves with the metaphor, from which each paradigm derives, and which has chiefly been used in the literary field. On the other hand, the fact itself that, with the passing of time, the analogical moulds proposed by management scholars and experts have increasingly moved away from “pure sciences” such as physics and biology, drawing closer to branches of learning the status of which is weak or at least of uncertain “exactness” (psychology, sociology, anthropology), is indicative of the growing inadequacy of science to understand the corporate world, as in any world affected by humans.

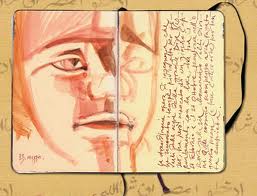

From this, it follows that management does not need a new paradigm, not a new absolute, axiomatic truth, but rather a new type of discourse. A discourse that talks to us of how to catch the emergence of new things, of how one learns to learn, of how the one is affected by the world we belong to and, at the same time, how the world is (also) the fruit of our creative contribution. Of how to return technology to its role as a tool and not a subject that watches over an order, in which man has become – literally – a subordinate. Of how then to recommence reflection on the aims, in addition to the means, that puts “art” at the centre, as is revealed to us at the highest level by poets, novelists and playwrights: by “humanists” in the Renaissance sense, storytellers, sensemakers through the novel, poetry, autobiography, the theatre and the cinema, but also the computer and even television. To social subjects such as management experts in general, interested in the affirmation of pseudo-methods, or paradigms, for the purpose of affirming their role as specialists, of necessary mediators, we counter with the authentic innovators: entrepreneurs, managers and, at their side, novelists, poets and directors. And also professors, if engaged in translating into practice the potential offered by humanistic thought for the creation of original interpretations of corporate culture. Better still, the hybrids, the contaminated and the symbiotics: the manager-writers, the personnel manager-directors and the CEO-painters. In short, any “mutant” innovator who does not set himself/herself as a deus ex machina outside of the work. The innovator grasps the emergence of a new world, knows how to interpret the entire picture from a few traces. But it is not a picture that he/she created. The innovator is part of the picture.

Go to Intro

Humanistic Management 2.0

- Home

- Origins of Humanistic Management in Italy: the ockhamist organization

- Agip Library

- The Shakespearian Company

- The Humanistic Management Manifesto

- Nothing twice. The Management seen through the poetry by Wisława Szymborska

- The Humanistic Management chair

- The In-Visible Corporation

- Web Opera

- ideaTRE60

- Postmodern Alice

- Founder & CEO of Humanistic Management 2.0

- News

- About Marco Minghetti

- Selected Excerpts

- Home

Feed RSS Subscriptions

Email subscriptions

About

Social media

Tag

Alice Alice in Wonderland Alice Wonderland Carroll Shakespeare Postmodern Baricco Deleuze Digital Awards Frank Kermode gary hamel George Steiner Hamlet Harold Bloom humanistic management labirinth Looking Glass management Management 2.0 Hackathon map Marco Minghetti poetry Postmodern Raymond Queneau Shakespeare Snark Stevenson Wislawa Szymborska Wonderland

Latest Comments